CubeLife History, Sources and Updates

When I first returned to making art in 1996 after a gap of around 15 years (I had suspended coloured drawing for writing between 1985-1996) the web was just taking off, and I thought about creating a multimedia piece based on drafts of written material I’d then been working on with mutating images and text as a spoken soundtrack; starting garbled but becoming clearer, accompanied by a montage of the environments where I worked, with clickable details. But I was aware that new digital art (known as “media art” for awhile) was then already being produced in two main formats: multimedia work with strong personal content, and impressive Shockwave, Flash or early JavaScript web material with high graphic content, often referencing the machines on which it was created. I didn’t want to work in a similar way, so instead decided to explore the roots of art-technology, while picking up a few threads lingering after my Fine Art degree, which used the mathematical patterns of magic squares (I only recently discovered that the late Vera Molnár used the same patterns). This work has now expanded into more mathematical areas too (see this presentation to Symmetry 2021), and into a magic square webapp created with my wife Fania. Our first paper “Creative Visualisation of Magic Squares” was published in the Proceedings of EVA London 2020 and one resulting print is now part of the CAS permanent collection. However, cubeLife uses magic cubes…

The exhibited cubeLife screen is blank—the work only starts when someone uses the heartbeat monitor (finger clip or later wireless hand grips), which enables participants to create a new magic cube and audio in virtual 3D space:

- heartbeat pulses “grow” the cube on-screen, after which its duration or life is calculated

- when input stops, the heartbeat-tethered cube is free to roam the virtual space and interact with the others (e.g. by flocking)

Each individual cube leaves tracks and combines its sound with cubes generate3d by others participants, building a non-repeating audio-visual presence. When it eventually dies, the cube’s tracks remain on screen and are gradually overwritten by new participants. So at any point, the work represents the collective heartbeat inputs of every participant. See static screen shots from between 1999-2011.

Becoming a Digital Artist ^

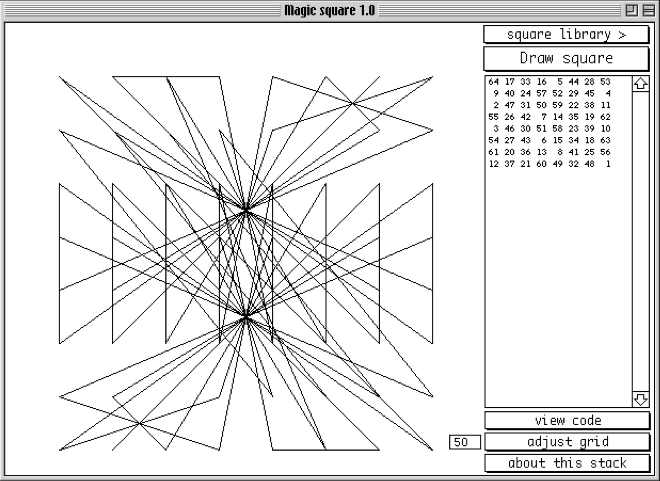

At that time I was beginning to combine creative art, hobby mathematics and computer skills. I was familiar with the fundamentals of programming logic, having cut my teeth on Apple’s venerable (and sadly discontinued) RAD Hypercard and it’s HyperTalk language, the syntax of which prepared me for other languages. I was also familiar with the basics of artificial life, certain mathematical patterns, and the images that can be formed from these. Java was then an emerging and conveniently cross-platform language, and (at the time) worked in web browsers. I wanted to explore a more mainstream language by collaborating with a far better programmer (Greg Turner), since scripting or RADs (like Director/Lingo, and x-talk languages like HyperTalk) then had limits, although the Hypercard programme (image, right) I wrote to research and test magic square patterns was a brilliant research tool before the advent of the web. I wanted to port the work to Live Code (then “Runtime Revolution”) but eventually worked with my wife Fania to rewrite and significantly extend it in JavaScript as a combined research tool and artwork generator itself—see squares.cubelife.org).

While searching for a structure and a medium, I received timely exposure to two digital art pioneers during seminars hosted by Loughborough University’s then-active Gallery of the Future, initiated by Ken Baynes (I got a foot in the door by being on the GoF board at the time).

One seminar was by the late Harold Cohen, who—using the programming language Lisp as a medium (when I naïvely asked why, he said it was good for Artificial Intelligence)—is an example of how computer science and art can interact—he programmed his machine AARON to create and colour paintings in his own style.

In the other seminar Paul Brown described how he adapted the basics of John Conway’s artificial life theory to create evolving images. At the time—coming from a design background in my former employment—I found it mildly encouraging that both preferred Apple machines for personal use (Cohen’s work also used other platforms) but what struck me most was how they’d pursued their lifetime’s work with impressive consistency.

After this, I trawled the web to find out what was being shown online (and discovered a now-dead review in Wired News of a 1997 New York show based on artist-modified 512K Macs, a homage to their digital art pedigree); I also read many of the then-sparse publications on the subject and found out about Furtherfield (1996, Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett)—one of the impressively active artist-led groups who rose with the advent of the web. However, although politically active in life, I was less socially-engaged in my artwork and already influenced by the loner careers of those older artists who had been working with technology since the 60’s and 70’s. I was beginning to combine creative art, hobby mathematics and computer skills and was familiar with the fundamentals of programming logic, having started with Logo (which used the “turtle” drawing approach that Harold Cohen began with), then moved to Apple’s venerable (and sadly discontinued) RAD Hypercard and it’s HyperTalk language, the syntax of which prepared me for other languages.

I was also familiar with the basics of artificial life, mathematical patterns, and the images that can be formed from these. Java was then an emerging cross-platform language, and (at the time) worked in web browsers. I wanted to explore a more mainstream language by collaborating with a better programmer (Greg Turner), since scripting or RADs (like Director/Lingo, and x-talk languages like HyperTalk) then had limits, although the Hypercard programme (see image) I wrote to research and test magic square patterns was a great research tool.

Code as a Tool ^

Custom programming allows for open, non-standard approaches and offers creative freedom. For cubeLife the heavy lifting was done in collaboration with Greg Turner as part of his Masters, and cubeLife is the result of that collaboration. Once development really began, my skills only took me so far—my role after starting the process by writing pseudocode—was to guide the logic and overall intent and process. The development of cubeLife is covered in the 2002 edition of Explorations in Art and Technology (see GoodReads) by Linda Candy and Ernest Edmonds, who ran various research projects within the HCI department at Loughborough Uni. Another collaborative art-computer-interface project, Sensor Grid with Mike Quantrill, produced the motion-tracking image on the cover. CubeLife is also covered in some detail in a 2004 paper On physiological computing with an application in interactive art, Section 4.3 (in “Interacting with Computers”). Ernest is also a long-career artist in the field, and his overall departmental and personal support was crucial. I later documented other work from that time in the 2018 edition.

Computing as a Medium ^

After listening to Harold Cohen and Paul Brown I realised that programming languages offered the optimum amount of control over the computer as a creative medium—I can design, create and adapt my own tools. Anything I can’t create alone I develop in collaboration. Work generated by commercial software can look formulaic or bandwagon, just as image manipulation tools can contain baggage visible in finished works because the code and environment of commercial applications can warp the creative path. Although AI has been present in art practice for some time, the recent rise in third-party AI tools has encouraged a new swathe of bandwagon work and ethical/critical concerns, as well as creative opportunities. But again, it is still software provided by a third party, and mostly under the ultimate control of large corporations.

CubeLife Research ^

Number

The use of number pattern in cultural symbolism is a rich resource, connecting apparently disparate material—for instance Leibniz’s binary numbers and the Chinese I Ching. As another example, Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I contains the first known representation of a magic square in European art, and his straddling of the mathematical and artistic worlds is an early example of art-science crossover. His famous engraving also hints at the lost Renaissance view of melancholy as a creative portal, originally explored fully in Frances Yates’ pioneering book The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, with a reference included in one of the exhibition display panels for cubeLife in 1999.

As well as the artistic and cultural sources informing cubeLife, I’m actively interested in certain aspects of the pure mathematics, e.g. number theory and combinatorics, two mathematical branches that can be used to examine magic squares and cubes (which have been followed up in papers and talks). During a separate residency at Loughborough University’s computer science department in the early 2000s, I started on a (discontinued) project with programmer Simon Nee in C++ to examine magic square structures, initiated communication with some of the web’s magic square specialists, started minor explorations, and finally after a long gap—created with with my wife Fania a magic square webapp which led to more recent presentations like this one and papers on the subject.

New Interfaces ^

At the HCI department at Loughborough I could pursue ideas in computer science that explored unconventional interfaces to computer-driven art (including the movement sensor grid on Silicon Graphics machines with Mike Quantrill, and other public work under the EmergencyArtLab). So one idea behind the single heartbeat-only input to cubeLife was to facilitate a warm instant biological connection to an otherwise cool mathematically-based structure. I liked the idea of bridging the schism between digital space and meatspace in a direct physical way, without resorting to a computer interface

. Everyone has a heartbeat so, for audiences, cubeLife aimed to be the most widely accessible work possible.

As far as I can tell, the exhibited version of CubeLife in 1999 appears to be the first heartbeat-driven interactive artwork, so I took some time to document it at the Archive of Digital Art. Before then, I can only find Bill and Louise Etra’s video work Heartbeat from 1973. Bill was a pioneering inventor of video effects machines. In the 1990s, Char Davies also created the physiological computing VR works Osmose and Ephemere (1995, 1998), using breath and balance sensors, which were very well-regarded at the time and ground-breaking in their use of the invisible interface concept—no mouse, keyboard or visible screen.

Possibilities ^

As of version 2 (around 2010, exhibited 2011) other options were added—again by collaborator Greg Turner—including flocking and online participation (not implemented at the time due to server security). I later swapped the finger-clip heartbeat monitor (which eventually failed) for more robust hand-grips, which work well but present other issues (e.g. hygiene concerns after the Covid pandemic, less widely-accessible). A safer form of heartbeat input is being considered, as well as necessary but non-trivial repairs to the three original host machines used during exhibitions. One current aim is to restore original functionality of the 1999 code (for archival purposes).

By including wider research into magic matrices, cubeLife therefore became a wider, long-term art and research project developing in as-yet unforeseen ways according to collaboration, ongoing investigations into magic matrices (both squares and cubes) and emerging technology.

At cubelife.org/galleries/ there are images from two exhibitions, as well as links to allied magic square research that expands on the more mathematical work that provided the foundation for cubeLife in the 1990s.