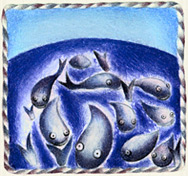

Our Special Fishes

Leaning over the harbour wall I could see my uncle amongst them. Fish with human faces. The first time I saw them I was three years old, and alarmed. But I remembered other human faces which sat on other unlikely bodies. Bugs Bunny, Mickey Mouse. Although the fish didn’t talk, my uncle seemed to accept them, just as he accepted everything else which existed around us. No matter, I thought, I’ve seen this sort of thing before. And although their appearance did make me uneasy at first, I too grew to accept them, because young children accept whatever they see in the world as reality. Besides, at that age no-one had told me any different, or at least, I hadn’t taken enough of it in to create a world-view which excluded such possibilities. But I knew that these were special.

They never wanted anything—food, I mean. They just arrived in the harbour and swam around, looking for company. He had been meeting them now for years, and occasionally he told us stories about how they first arrived, and why we should never hunt them for food. The fishermen always took special care not to harm them in the nets, but they rarely got caught anyway, not like sharks or other big fish, and those that did were usually sick or in need of care.

Still, I had cartoon characters in my mind, and sometimes I found the fish unsettling. I couldn’t tell whether or not we were all simply seeing something perfectly commonplace in the wrong way; looking at some ordinary creature with the wrong eyes. I hadn’t seen any fish like this in pictures. Yet I could not say for certain that the village was deluding itself. After all, I had seen them too, and I had no cause to doubt my senses. So I grew up, worked when I was old enough, and still the fish came; just as often. Over the years, I learned to accept them, and felt privileged that they should choose our harbour.

There was a caravan site on top of the hill and, during the holidays, people often wandered away from the beaches and down into our tiny harbour while we were working. There wasn’t much to see—although I suppose it was picturesque enough—so they didn’t stay long, after taking their pictures. We were too busy to notice them, really.

My uncle never came out with us after his seventieth birthday, but spent most of his time in the harbour doing easy but essential jobs. He continued to ignore the few holidaymakers who came this way. The road was a simple rough track, so he knew there would only ever be six or seven at a time at most; not enough to look up from his work to see if they were interfering with anything.

When we returned one evening, he was up to his waist in the water. I knew what he was doing. He only ever went into the water when the fish came. It was hard to see their faces unless you waded right in, amongst them. I glanced over as we were mooring the boat and unloading the catch. I heard someone with a camera and a child say:

“Look at that man in the water with those big fish!”